The Global Positioning System (GPS) represents a ubiquitous technology that underpins countless aspects of modern life, from navigation and surveying to scientific research and emergency services. While its utility is widely recognized, the intricate mechanisms governing its operation are often less understood. At its core, GPS leverages a fundamental constant of the universe: the speed of light. This article delves into the principles by which GPS satellites utilize this constant to provide precise location data, examining the architecture, signal transmission, and the relativistic considerations that ensure its accuracy.

The GPS Constellation: A Network in Space

The GPS infrastructure is comprised of several distinct segments working in concert to deliver positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) information.

Space Segment: The Orbital Clock Towers

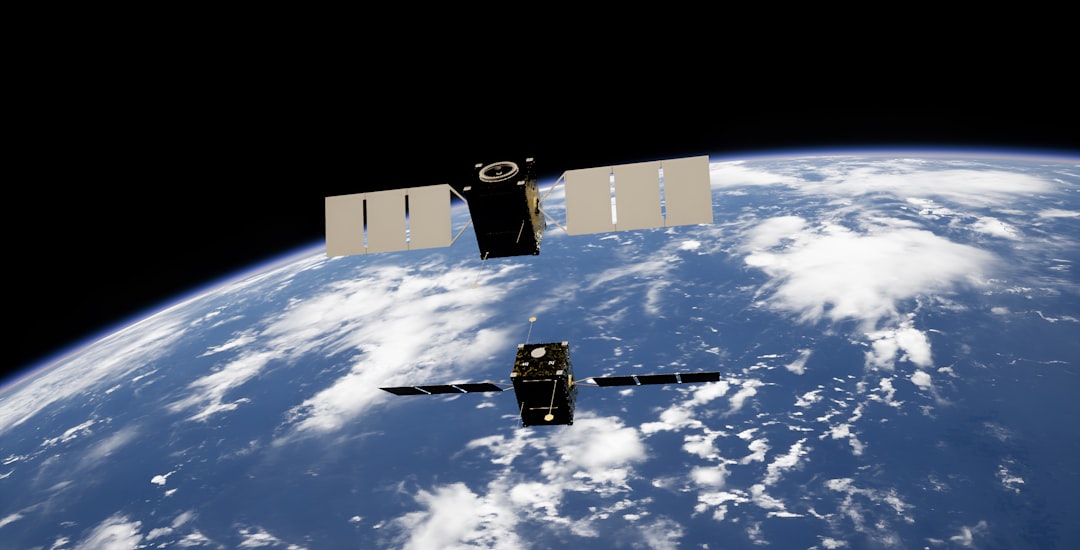

The most visible component of GPS is the space segment, which consists of a constellation of Earth-orbiting satellites.

Satellite Design and Orbit

Currently, the operational GPS constellation consists of at least 31 active satellites, though historically this number has varied. These satellites orbit the Earth in medium Earth orbit (MEO) at an altitude of approximately 20,200 kilometers (12,550 miles). Their orbital planes are specifically designed to ensure that at least four satellites are visible from almost any point on the Earth’s surface at any given time. This redundancy is crucial for robust and continuous signal reception. Each satellite is equipped with highly accurate atomic clocks – typically rubidium and cesium clocks – which are fundamental to the system’s precision.

Signal Transmission

Each GPS satellite continuously broadcasts signals containing several key pieces of information:

- Pseudorandom Noise (PRN) codes: These unique digital codes enable a receiver to identify individual satellites and to accurately measure the time it took for the signal to travel from the satellite to the receiver.

- Navigation Message: This data, transmitted at a much slower rate, contains crucial information such as the satellite’s ephemeris (its precise orbital position and trajectory for a given time), clock corrections, and the constellation’s health status.

Control Segment: The Earthly Orchestrators

The control segment is responsible for maintaining the health and accuracy of the GPS constellation.

Master Control Station

The primary facility, the Master Control Station (MCS), is located at Schriever Space Force Base in Colorado. This station performs critical functions such as monitoring the satellites’ performance, calculating their precise orbits and clock drifts, and uploading navigation messages.

Monitor Stations and Ground Antennas

A global network of monitor stations tracks the GPS satellites’ signals. These stations collect data on the satellites’ ephemeris and clock biases, which are then transmitted to the MCS. Ground antennas are used by the MCS to upload updated navigation data and commands to the satellites. This continuous monitoring and adjustment are paramount for maintaining the system’s accuracy.

User Segment: The Receivers on the Ground

The user segment encompasses all GPS receivers, from dedicated navigation devices to integrated modules in smartphones.

Receiver Functionality

GPS receivers do not send signals to satellites. Instead, they passively listen for signals from multiple satellites. By simultaneously receiving signals from at least four satellites, a receiver can calculate its position in three dimensions (latitude, longitude, and altitude) and also provide a highly accurate time synchronized to the GPS system.

Principles of Position Determination: The Essence of Range Measurement

The core principle behind GPS positioning is trilateration, a geometric technique that uses distance measurements to pinpoint a location.

Time of Flight: The Speed of Light as a Ruler

Each GPS satellite acts as a precisely synchronized “clock tower” broadcasting its exact time. A GPS receiver, acting as a “listener,” starts its own clock when it receives a signal. The time difference between the satellite’s broadcast time and the receiver’s reception time, multiplied by the speed of light, yields the distance (or range) to that satellite.

Pseudoranges

Since the receiver’s internal clock is typically not as accurate as the atomic clocks on board the satellites, there is an inherent clock offset in the receiver. This means the immediate distance calculated is a “pseudorange,” not a true range. The receiver uses the signals from a minimum of four satellites to solve for its three-dimensional position (x, y, z) and its receiver clock offset. In essence, the fourth satellite’s signal allows the receiver to determine how much its internal clock is off, effectively calibrating itself against the precise timing of the GPS system.

The Role of Universal Time Coordinated (UTC)

GPS time is a highly stable time scale maintained by the control segment. It is synchronized with UTC, the international standard for timekeeping, though it does not incorporate leap seconds. The GPS navigation message includes parameters that allow receivers to convert GPS time to UTC, enabling seamless integration with other time-sensitive applications.

Relativistic Effects: Adjusting for Einstein

While the speed of light is constant, the effects predicted by Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity play a significant role in GPS accuracy. Ignoring these effects would lead to rapid and substantial errors in position calculations.

Special Relativity: Time Dilation

According to special relativity, moving clocks run slower than stationary clocks. Each GPS satellite is traveling at approximately 14,000 kilometers per hour (8,700 miles per hour) relative to an observer on Earth. This high velocity causes the atomic clocks on board the satellites to tick slower than a hypothetical stationary clock on Earth. This effect would cause the satellite clocks to fall behind by about 7 microseconds per day.

General Relativity: Gravitational Time Dilation

General relativity posits that clocks in stronger gravitational fields run slower than clocks in weaker gravitational fields. Since GPS satellites are at a much higher altitude than observers on Earth, they experience a weaker gravitational field. Consequently, their clocks run faster than clocks on Earth. This effect would cause the satellite clocks to gain approximately 45 microseconds per day.

Net Relativistic Correction

When both special and general relativistic effects are considered, the net effect is that the satellite clocks run faster than Earth-bound clocks by approximately 38 microseconds per day (45 – 7 = 38). To counteract this, the atomic clocks on GPS satellites are deliberately set to run slightly slower before launch, by approximately 38.7 microseconds per day. This pre-compensation ensures that from an Earth-bound perspective, the satellite clocks appear to be ticking at the correct rate. Without this relativistic adjustment, the accumulated error would be kilometers per day, rendering the system practically useless.

Sources of Error and Mitigation Strategies

Despite the sophistication of the GPS system, various factors can introduce errors into position calculations. Understanding these sources is crucial for developing robust and accurate GPS applications.

Atmospheric Delays

The GPS signal, traveling at the speed of light in a vacuum, slows down and refracts as it passes through the Earth’s atmosphere.

Ionospheric Delay

The ionosphere, a layer of charged particles in the upper atmosphere, affects the speed of radio waves. This delay is frequency-dependent, meaning signals at different frequencies are affected differently. Modern GPS receivers often utilize dual-frequency reception (e.g., L1 and L2 frequencies) to model and correct for ionospheric delays, as the difference in delay between the two frequencies can be used to estimate the total delay.

Tropospheric Delay

The troposphere, the lower part of the atmosphere containing weather phenomena, also causes signal delays. Unlike the ionosphere, this delay is not frequency-dependent and is primarily influenced by atmospheric pressure, temperature, and humidity. Receivers use atmospheric models to estimate and correct for tropospheric delays, or in more advanced applications, ground-based augmentation systems (GBAS) or satellite-based augmentation systems (SBAS) can provide real-time corrections.

Multipath Effect

Multipath occurs when GPS signals bounce off objects like buildings or terrain before reaching the receiver antenna. This causes the signal to travel a longer path, leading to an overestimation of the distance to the satellite. Advanced receiver designs incorporate techniques to mitigate multipath, such as using specialized antennas that reject signals coming from certain angles or employing sophisticated signal processing algorithms.

Satellite Clock and Ephemeris Errors

Although meticulously monitored, there can be minor inaccuracies in the satellite’s reported clock time and orbital position. The control segment continuously uploads updated ephemeris and clock correction data to minimize these errors.

Receiver Noise

The internal electronics of a GPS receiver introduce a certain level of noise, which can affect the precision of signal measurements. Higher quality receivers typically have lower noise levels.

Geometric Dilution of Precision (GDOP)

GDOP describes the geometrical arrangement of visible satellites relative to the receiver. A poor satellite geometry, where satellites are clustered together in the sky, can amplify ranging errors, leading to reduced positioning accuracy. Conversely, a wide spread of satellites across the sky (low GDOP) provides better accuracy. Receivers continuously calculate GDOP and will indicate when the geometry is suboptimal.

Beyond Terrestrial Navigation: Diverse Applications

The precision and reliability offered by GPS, built upon the fundamental speed of light and meticulously accounted for relativistic effects, have extended its utility far beyond simple navigation.

Scientific Research

GPS data is instrumental in various scientific fields.

Geodetics and Plate Tectonics

Precise measurements of Earth’s crustal deformation over time, facilitated by stationary GPS receivers, allow scientists to monitor plate tectonic movements, earthquake zones, and volcanic activity. This provides critical insights into geological processes.

Atmospheric Studies

By analyzing the delays in GPS signals as they pass through the atmosphere, scientists can infer information about atmospheric conditions, such as water vapor content, which is valuable for weather forecasting and climate research.

Precision Agriculture

In agriculture, GPS enables highly efficient farming practices.

Guidance Systems

GPS-guided tractors and other machinery can follow precise paths, minimizing overlap and skips, thus optimizing the use of fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds.

Variable Rate Application

Farmers can use GPS to create detailed maps of their fields, allowing for variable rate application of inputs based on soil conditions or crop health, leading to reduced waste and increased yields.

Emergency Services

GPS plays a vital role in enhancing emergency response.

Location for 911 Calls

Enhanced 911 (E911) systems utilize GPS data from mobile phones to pinpoint the location of callers, significantly reducing response times for emergency services.

Search and Rescue

GPS-enabled devices are used in search and rescue operations to track individuals or to guide rescue teams to distress signals in remote areas.

Timing and Synchronization

The highly accurate time provided by GPS is essential for many systems.

Telecommunications and Power Grids

GPS timing signals are used to synchronize cellular networks and power grids, ensuring precise operation and preventing disruptions. Financial transactions also rely on GPS for accurate time-stamping.

The Future of Satellite Navigation: Modernization and Global Systems

The GPS constellation has undergone continuous modernization, with the deployment of newer satellites broadcasting additional signals and offering enhanced capabilities. Furthermore, other global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) have emerged, contributing to a more robust and resilient PNT landscape.

GPS Modernization

Modernization efforts for GPS include the deployment of new civilian signals (e.g., L2C, L5) that offer improved accuracy, robustness, and resistance to interference. These signals also provide further redundancy and allow for more sophisticated ionospheric correction techniques.

Other GNSS

Several other countries and regions have developed or are developing their own GNSS, including:

GLONASS (Russia)

Russia’s GLONASS system is fully operational and provides global coverage.

Galileo (Europe)

The European Union’s Galileo system is a civilian-controlled GNSS designed to offer highly accurate and reliable positioning services.

BeiDou (China)

China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS) has achieved global coverage and continues to expand its capabilities.

These multiple GNSS constellations, operating independently yet often interoperably, offer increased redundancy and improved accuracy, particularly in urban canyons or challenging environments where line-of-sight to a sufficient number of satellites from a single system may be obstructed. The ongoing evolution of these systems underscores the critical importance of leveraging the speed of light for ever more precise and reliable positioning across the globe.

FAQs

How do GPS satellites use the speed of light to determine location?

GPS satellites transmit signals that travel at the speed of light to receivers on Earth. By measuring the time it takes for these signals to reach the receiver, the system calculates the distance between the satellite and the receiver, enabling precise location determination.

Why is the speed of light important for GPS accuracy?

The speed of light is a constant and extremely fast, allowing GPS systems to measure signal travel times with high precision. Accurate timing is crucial because even tiny errors in time measurement can lead to significant errors in position calculation.

How do GPS receivers calculate distance from satellites using the speed of light?

GPS receivers record the time a signal was sent by the satellite and the time it was received. By multiplying the time difference by the speed of light, the receiver calculates the distance to the satellite, which is essential for triangulating the receiver’s exact position.

Do GPS satellites account for relativistic effects related to the speed of light?

Yes, GPS satellites account for relativistic effects such as time dilation caused by their high speeds and weaker gravitational field compared to Earth’s surface. These effects influence the satellite clocks and must be corrected to maintain accurate positioning.

Can the speed of light vary and affect GPS performance?

The speed of light in a vacuum is constant and does not vary, which is fundamental to GPS accuracy. However, signals can slow down slightly when passing through the Earth’s atmosphere, and GPS systems use models to correct for these delays to maintain precise location data.