The concept of spacetime geometry, traditionally associated with the large-scale gravitational phenomena described by general relativity, extends into a more granular domain when considering the trajectories of individual particles. This article delves into the exploration of ‘worldline spacetime geometry,’ a framework that examines the geometric properties intrinsic to the path of a particle or object through spacetime, known as a worldline. This perspective offers a detailed and localized understanding of an object’s interaction with the underlying fabric of the universe, distinct from global spacetime structures.

At its core, a worldline is the path traced by an object, regardless of its mass or composition, through four-dimensional spacetime. It is not merely a trajectory in space over time but an irreducible geometric entity. Understanding the worldline as such allows for a re-evaluation of how quantities like length, curvature, and torsion manifest at the micro-level, bridging the gap between quantum mechanics and general relativity in a conceptual sense. You can learn more about the block universe theory in this insightful video.

Defining the Worldline

A worldline is mathematically represented as a curve in spacetime. For a particle with position coordinates $x^i(t)$ at time $t$, its worldline can be parameterized by proper time $\tau$, a scalar quantity invariant under Lorentz transformations. This parametrization yields $x^\mu(\tau)$, where $\mu$ runs from 0 to 3, representing time and the three spatial dimensions.

The Role of Proper Time

Proper time serves as the natural parameter for timelike worldlines, which correspond to massive particles. It is the time elapsed on a clock carried by the object itself. For lightlike worldlines, which represent massless particles like photons, proper time is undefined or zero, and an affine parameter is typically used instead. Proper time is a crucial concept, as it directly relates to the perceived duration of events from the particle’s internal frame of reference, offering a foundational metric for its journey.

Worldlines in Different Spacetimes

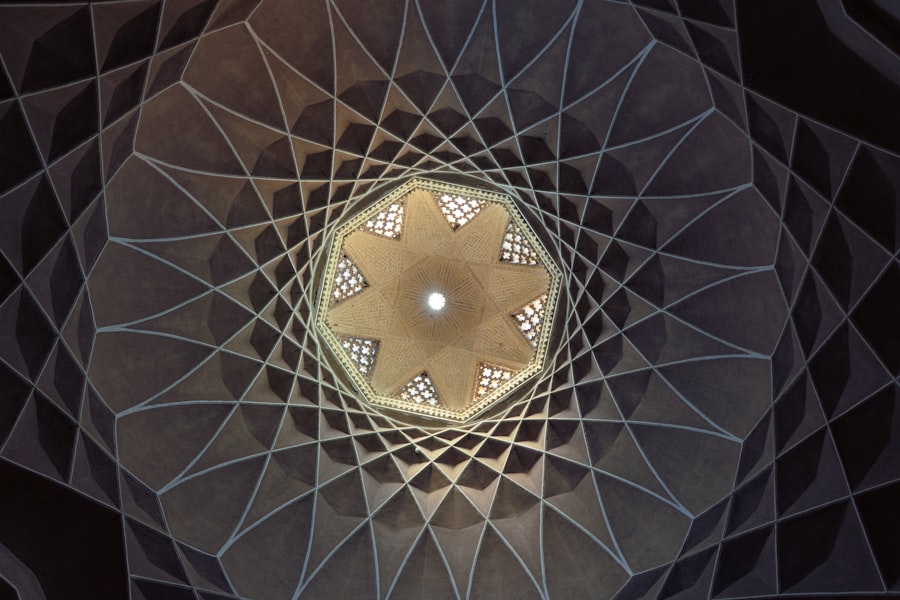

The geometry of a worldline is inherently dependent on the background spacetime in which it exists. In flat Minkowski spacetime, worldlines are “straight” (geodesics) in the absence of forces, whereas in curved spacetime, such as around a black hole, they deviate from what would be a straight path in flat space. This deviation is not due to a force in the classical sense, but rather a manifestation of the spacetime curvature itself.

Worldline spacetime geometry is a fascinating concept in theoretical physics that explores the paths taken by objects through spacetime, revealing insights into the nature of time and gravity. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can refer to an insightful article that discusses the implications of worldline geometry on our perception of time and its relationship with the universe. To read more, visit this article for an engaging exploration of these ideas.

Intrinsic Geometric Properties of Worldlines

Just as a curve in Euclidean space possesses intrinsic geometric properties like length and curvature, so too does a worldline in spacetime. These properties are observer-independent and provide crucial insights into the particle’s motion and its interaction with the spacetime fabric.

Worldline Length: The Proper Time Integral

The length of a timelike worldline between two events $A$ and $B$ is given by the integral of the proper time interval $\mathrm{d}\tau$ along the path: $L = \int_A^B \mathrm{d}\tau$. This length corresponds to the total proper time elapsed for an object traveling along that worldline. It is a maximized quantity for free-falling objects (geodesics) between two fixed events in spacetime, a concept central to the principle of maximal aging in general relativity.

Worldline Curvature: Deviation from Straightness

The curvature of a worldline quantifies how much it deviates from a “straight” path in spacetime. For a massive particle, this curvature is related to the acceleration experienced by the particle. In general relativity, a particle subject to gravity but no other forces follows a geodesic, which locally appears “straight” in the curved spacetime. Therefore, in the absence of non-gravitational forces, a worldline’s curvature implies the presence of such forces acting on the particle, or the spacetime itself is highly dynamic.

Worldline Torsion: A Measure of Twist

While curvature describes the bending of a worldline within its osculating plane, torsion describes how this plane “twists” as one moves along the worldline. In 3D Euclidean geometry, torsion measures the extent to which a curve departs from being planar. In spacetime, the interpretation is more complex and less commonly discussed for general worldlines, but it can provide insights into higher-order deviations from geodesic motion or the presence of complex external fields influencing the particle’s trajectory. Its direct physical interpretation often requires specific geometric contexts or specialized metrics.

Worldlines and the Principle of Geodesic Motion

A cornerstone of general relativity is the principle that massive, uncharged, spinless particles not subject to non-gravitational forces follow timelike geodesics. These are the “straightest possible” paths in curved spacetime. This principle elevates the concept of a worldline from a mere trajectory to a fundamental consequence of spacetime geometry.

Geodesics as Paths of Extremal Proper Time

As previously mentioned, timelike geodesics between two fixed events maximize the proper time elapsed. Imagine two cities on a globe; the shortest distance between them is along a great circle. Similarly, in spacetime, a geodesic is the “longest” path in terms of proper time for an object. This is counter-intuitive if one thinks in terms of Euclidean distance, but it stems from the Lorentzian signature of the spacetime metric. For lightlike particles, geodesics are paths of zero proper time (null geodesics) and represent paths of light.

Deviations from Geodesic Motion

Any deviation of a worldline from a geodesic path implies the action of a non-gravitational force, such as electromagnetic forces, weak and strong nuclear forces, or contact forces. These external influences “bend” the worldline away from its natural, geodesic trajectory, introducing acceleration as observed by an inertial observer. The relationship between force, mass, and the deviation from geodesic motion directly encapsulates Newton’s second law within a relativistic framework.

The Role of Initial Conditions

The specific worldline followed by a particle is determined not only by the background spacetime geometry but also by its initial position and velocity – its initial conditions. These conditions dictate which specific geodesic, or non-geodesic path under external forces, the particle will trace through spacetime. The deterministic nature of classical worldlines underscores the predictive power of general relativity.

Quantum Aspects and Worldline Formalism

While worldlines are fundamentally classical concepts, there exist formalisms that attempt to bridge the gap into the quantum realm. The “worldline formalism” in quantum field theory, for instance, reformulates quantum amplitudes as sums over paths in spacetime, inspired by Feynman’s path integral. This approach aims to provide a more intuitive geometric picture for quantum phenomena.

Feynman’s Path Integral and Worldlines

Richard Feynman’s path integral formulation of quantum mechanics postulates that a quantum particle propagates between two points by “taking all possible paths,” each path contributing to the total probability amplitude with a phase determined by its action. In a relativistic context, these “paths” can be interpreted as worldlines, each with its own proper time and associated action. The traditional quantum field theory approach calculates scattering amplitudes using perturbation theory and Feynman diagrams, which can be seen as abstractions of worldline interactions.

The Worldline Formalism for Quantum Fields

The worldline formalism provides an alternative, often more compact and elegant, way to calculate quantum amplitudes. It treats quantum fields as if they are “propagating” along worldlines, even for gauge fields like photons where the traditional particle concept is more nuanced. This approach is particularly powerful for calculating effective actions and scattering amplitudes in quantum electrodynamics (QED) and quantum chromodynamics (QCD), offering a perspective that emphasizes the particle’s trajectory rather than the field’s evolution.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its elegance, the direct application of the worldline formalism to quantum gravity remains a significant challenge. The difficulty lies in quantizing the spacetime metric itself, which fundamentally alters the geometric interpretation of worldlines. Understanding how particles perceive and interact with a quantized spacetime would require a deeper understanding of the interplay between geometry and quantum mechanics, potentially leading to new insights into the nature of reality at its most fundamental scales.

Worldline spacetime geometry is a fascinating topic that delves into the intricate relationship between time and space as described by the theory of relativity. For those interested in exploring this concept further, a related article can provide deeper insights into how worldlines represent the paths of objects through spacetime. You can read more about this intriguing subject in the article found here, which discusses various aspects of spacetime and its implications for our understanding of the universe.

Applications and Observational Signatures

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proper Time (τ) | Time measured along the worldline by a clock moving with the particle | Varies depending on observer and path | seconds |

| Spacetime Interval (s²) | Invariant interval between two events on the worldline | Positive (timelike), zero (lightlike), or negative (spacelike) | meters² or seconds² (using c=1) |

| Four-Velocity (U^μ) | Rate of change of position in spacetime with respect to proper time | Norm equals 1 (in units where c=1) | dimensionless (normalized) |

| Four-Acceleration (A^μ) | Rate of change of four-velocity along the worldline | Varies with forces acting on the particle | meters/second² (in natural units) |

| Curvature of Worldline | Measure of how the worldline deviates from a geodesic | Zero for free-fall (geodesic) motion | 1/meters |

| Proper Length | Length of a spatial segment measured in the rest frame | Depends on spatial separation and frame | meters |

The conceptual framework of worldline spacetime geometry is not merely a theoretical construct; it has profound implications for understanding observable phenomena, from the paths of planets to the predictions of gravitational waves.

Gravitational Lensing and Worldlines of Light

One of the most striking observational consequences of curved spacetime, and thus worldline geometry, is gravitational lensing. When light from a distant source passes near a massive object (like a galaxy or a black hole), its worldline is bent, causing the light to be deflected. This acts like a cosmic lens, distorting images, creating multiple images of a single source, or magnifying distant objects. The “bending” of light’s worldline is a direct manifestation of spacetime curvature.

Worldlines in Binary Systems and Gravitational Waves

Consider the worldlines of two massive objects orbiting each other, such as in a binary black hole system. These objects follow complex, accelerating worldlines within the spacetime warped by their mutual presence. Their motion generates ripples in spacetime known as gravitational waves. The precise geometry of these worldlines, as predicted by general relativity, determines the amplitude, frequency, and phase of the emitted gravitational waves, which are now routinely detected by observatories like LIGO and Virgo. Analyzing these gravitational wave signals allows us to infer the properties of the compact objects and test general relativity in extreme gravitational environments.

Relativistic Geodesy and Precise Timing

On Earth, the precise timing and positioning data from systems like GPS rely on a sophisticated understanding of relativistic effects, including the slight curvature of spacetime induced by Earth’s mass. The worldlines of satellites and the light signals they emit are influenced by this curvature. Without accounting for these relativistic deviations from flat spacetime geometry, GPS systems would accumulate errors of kilometers per day, highlighting the practical importance of understanding worldline geometry in even everyday technologies.

In conclusion, the exploration of worldline spacetime geometry offers a powerful and nuanced perspective on how objects, from elementary particles to massive astrophysical bodies, traverse the universe. By focusing on the intrinsic geometric properties of these trajectories – their length, curvature, and the subtle interplay with the background spacetime – we gain deeper insights into the fundamental principles governing motion and interaction. From the classical elegance of geodesic motion to the quantum intricacies of path integrals, and from the observable bending of light to the ripples of gravitational waves, the worldline concept serves as a unifying thread in our quest to comprehend the cosmos. As we continue to probe the universe with increasing precision, the detailed study of worldline geometry will undoubtedly yield further revelations about the fabric of reality itself.

FAQs

What is worldline spacetime geometry?

Worldline spacetime geometry is a concept in physics that describes the path an object takes through four-dimensional spacetime, combining its position in space and time into a single continuous trajectory.

How does a worldline differ from a regular path?

A worldline represents an object’s history in spacetime, including both spatial position and temporal progression, whereas a regular path typically refers only to spatial movement without explicit consideration of time.

Why is worldline important in the theory of relativity?

In relativity, worldlines help visualize and analyze how objects move through spacetime, illustrating concepts like time dilation, simultaneity, and causality by showing how events are connected in both space and time.

What does the geometry of a worldline tell us?

The geometry of a worldline reveals information about the object’s velocity, acceleration, and the effects of gravitational fields, as well as the causal relationships between events along the trajectory.

Can worldlines intersect or cross each other?

In general, worldlines of different objects can intersect if they meet at the same event in spacetime, but a single object’s worldline cannot intersect itself because that would imply the object being in two places at the same time.

How is worldline spacetime geometry represented mathematically?

Worldlines are represented using four-dimensional coordinates in spacetime, often described with tensors and metrics in the framework of general relativity to account for curvature caused by mass and energy.

What role do worldlines play in understanding black holes?

Worldlines help describe how objects move near black holes, showing how spacetime curvature affects trajectories and how events like crossing the event horizon are represented in spacetime geometry.

Is worldline spacetime geometry applicable only to particles?

No, worldline spacetime geometry applies to any object or observer moving through spacetime, including particles, light rays, and even extended objects, though extended objects may require more complex descriptions.

How does the concept of proper time relate to worldlines?

Proper time is the time measured by a clock moving along with an object and corresponds to the length of the object’s worldline between two events, providing an invariant measure of elapsed time in spacetime geometry.

What tools or diagrams are used to visualize worldline spacetime geometry?

Spacetime diagrams, such as Minkowski diagrams, are commonly used to visualize worldlines, plotting time on one axis and space on another to illustrate the motion and causal relationships of events.