The quest to reconcile Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which describes gravity on large scales, with the principles of quantum mechanics, which governs the microscopic world, remains one of the most significant challenges in modern physics. This endeavor, often referred to as the search for a theory of quantum gravity, aims to provide a unified description of the universe at all scales. Among the various theoretical frameworks developed to tackle this problem, Causal Dynamical Triangulations (CDT) has emerged as a compelling and distinct approach. CDT is a non-perturbative approach to quantum gravity that builds upon the mathematical framework of dynamical triangulations, incorporating causality as a fundamental ingredient. This article aims to explore the core concepts of CDT, its key features, and its potential implications for our understanding of spacetime and gravity at the quantum level.

The Fundamental Problem: Unifying Gravity and Quantum Mechanics

The Breakdown of Classical Gravity at Small Scales

General relativity, while incredibly successful in describing the behavior of gravity in macroscopic systems such as planets, stars, and galaxies, encounters significant difficulties when applied to phenomena at extremely small scales, such as those found near black hole singularities or at the very beginning of the universe. At these scales, quantum effects become dominant, and the smooth, continuous spacetime predicted by general relativity is expected to break down, giving way to a more granular, probabilistic structure. A key issue arises when attempting to quantize general relativity directly. The standard quantization procedures, which work remarkably well for other fundamental forces like electromagnetism, lead to uncontrollable infinities (non-renormalizability) when applied to gravity. This suggests that a fundamentally different approach is needed. You can learn more about managing your schedule effectively by watching this video on block time.

The Need for a Quantum Description of Spacetime

Just as a photograph captures a still image of reality, classical general relativity describes spacetime as a static background upon which physical phenomena unfold. However, at the quantum level, this picture is incomplete. Quantum mechanics dictates that not only matter and energy but also spacetime itself should be subject to quantum fluctuations. Imagine trying to build a house on a foundation that is constantly shimmering and shifting, where the very bricks and mortar are subject to quantum uncertainty. This is the kind of challenge quantum gravity seeks to address. A quantum theory of gravity would provide a consistent framework for understanding the structure and evolution of spacetime at the most fundamental level, including extreme environments where both gravity and quantum effects are crucial.

Introducing Dynamical Triangulations: A Discretized Approach

The Concept of Discretization

To grapple with the complexities of quantum gravity, many theoretical approaches opt for a strategy of discretization. Instead of treating spacetime as a continuous manifold, these approaches divide it into a multitude of interconnected, discrete units. Think of it like moving from a watercolor painting, where colors blend smoothly, to a mosaic, where the image is composed of tiny, discrete tiles. This discretization allows for the application of computational techniques and statistical mechanics to study the quantum properties of spacetime.

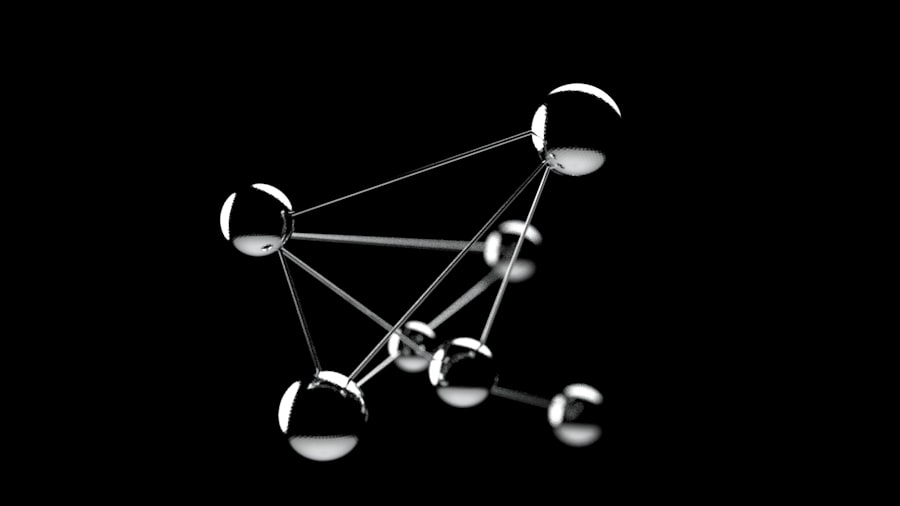

Building Blocks of Spacetime: Simplices

In the context of dynamical triangulations, the fundamental building blocks are called “simplices.” For a (3+1)-dimensional spacetime (three spatial dimensions and one time dimension), these simplices are four-dimensional generalizations of triangles and tetrahedrons, known as 4-simplices. These 4-simplices are glued together along their boundaries to form a discrete spacetime geometry. The “dynamical” aspect comes from the fact that the configuration of these simplices, and thus the geometry of spacetime itself, is not fixed. Instead, it is allowed to fluctuate, embodying the quantum nature of spacetime. The theory considers all possible ways these simplices can be assembled, weighted by a quantum mechanical amplitude.

The Role of Path Integrals

The mathematical machinery typically used to describe quantum systems is the path integral formalism, pioneered by Richard Feynman. This formalism states that the probability of a system transitioning from one state to another is given by summing over all possible “paths” or histories the system could take, each path weighted by a factor related to its action. In dynamical triangulations, this translates to summing over all possible spacetime configurations formed by the simplices that connect an initial state to a final state. This grand sum over all possible geometries is the heart of the quantum gravitational calculation.

Causal dynamical triangulations (CDT) is an intriguing approach to quantum gravity that seeks to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics by using a lattice-like structure to model spacetime. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article that delves into the implications and applications of CDT can be found at My Cosmic Ventures. This resource provides valuable insights into the ongoing research and developments in the field, making it a great starting point for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of this fascinating area of theoretical physics.

Causal Dynamical Triangulations: Injecting Causality

The Problem of Unordered Spacetime in Standard Dynamical Triangulations

Classical dynamical triangulations, while providing a discrete framework, often struggle with preserving the fundamental concept of causality – the notion that effects cannot precede their causes. In many discretized models, the “time” ordering of events can become ambiguous or even completely lost. This is akin to having a collection of photos from a movie but being unsure of the exact sequence in which they occurred, making it impossible to understand the narrative. This ambiguity makes it difficult to recover the familiar relativistic description of spacetime.

Imposing a Fixed Time Foliation

Causal Dynamical Triangulations fundamentally address this issue by imposing a strict causal structure. This is achieved by dividing spacetime into discrete “time slices.” Imagine spacetime as a stack of poker chips, where each chip represents a moment in time. In CDT, the simplices are arranged such that their connections respect a clear temporal ordering. This means that a simplex in one time slice can only connect to simplices in the same time slice or in the subsequent time slice, never to a prior one. This temporal constraint ensures that the fundamental causality is built into the very fabric of the discretized spacetime.

The Hamiltonian Approach and Transition Amplitudes

The imposition of causality in CDT naturally leads to a formulation that resembles a quantum mechanical Hamiltonian system. The theory calculates transition amplitudes between different spatial geometries at successive time slices. This allows for a more structured approach to calculating how spacetime evolves quantum mechanically, akin to understanding the evolution of a quantum system from one state to another over time. The “dynamically triangulated” spacetime is not just a random collection of geometric pieces; it is a dynamically evolving structure with a built-in arrow of time.

The Emergence of Spacetime Phases in CDT

Quantum Fluctuations and Geometric Configurations

The power of CDT lies in its ability to explore the vast landscape of possible spacetime configurations. By performing the path integral over all valid causal triangulations, the theory can reveal which spacetime geometries are most probable. These probabilities can be thought of as weights assigned to different “states” of spacetime. When physicists analyze the results of CDT simulations, they often observe distinct “phases” of spacetime, each characterized by different dominant geometric behaviors.

The De Sitter Phase: A Universe of Expanding Dimensions

One of the most significant findings from CDT research is the emergence of a phase that resembles a de Sitter spacetime. A de Sitter universe is one that is uniformly accelerating and expanding. This phase is characterized by a macroscopic, albeit dynamically generated, four-dimensional spacetime that exhibits a positive cosmological constant. Astonishingly, this de Sitter phase emerges from the collective behavior of the microscopic simplices, suggesting that the large-scale structure of our universe might be a consequence of the underlying quantum gravitational dynamics. This is a powerful demonstration of emergence, where macroscopic properties arise from the collective behavior of microscopic constituents, much like the wetness of water emerges from the interactions of individual molecules.

The Power-Law Phase: A Different Kind of Emergence

Another important phase observed in CDT is the “power-law” phase. In this phase, the spectral dimension of spacetime, a measure of how easily one can move around in spacetime, behaves differently. This phase has been investigated for its potential connections to different cosmological models and different early-universe scenarios. Understanding these different phases is crucial for determining which, if any, accurately describes our observable universe and its evolutionary history.

Computational Tools and Simulative Approaches in CDT

Monte Carlo Methods: Navigating the Path Integral

The path integral in CDT involves summing over an astronomically vast number of possible spacetime configurations. Directly performing such a sum is computationally intractable. To overcome this, CDT researchers heavily rely on sophisticated computational techniques, particularly Monte Carlo simulations. These methods allow physicists to efficiently sample the most probable configurations and estimate the relevant physical quantities, much like a pollster using a sample of voters to gauge the overall sentiment of an election.

Lattice Gauge Theory Analogies

The discretized nature of CDT also allows for analogies with concepts from lattice gauge theory, a successful framework for studying quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of the strong nuclear force. In lattice gauge theory, spacetime is discretized into a lattice, and the quantum fields are defined on the lattice points. While CDT deals with the geometry of spacetime itself, the computational strategies and analytical techniques developed in lattice gauge theory provide valuable inspiration and tools for CDT calculations.

Large-Scale Simulations and the Quest for Universality

As computational power has increased, so has the scale and complexity of CDT simulations. Researchers are able to simulate larger and larger spacetime volumes, allowing them to probe the behavior of spacetime at scales closer to those relevant for cosmology. The goal is to identify universal properties of quantum gravity that do not depend on the specific details of the discretization, making the results robust and predictive.

Causal dynamical triangulations is an intriguing approach to quantum gravity that seeks to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics by using a lattice-like structure of spacetime. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article discusses the implications of this theory on our understanding of the universe and its fundamental nature. You can read more about it in this insightful piece on mycosmicventures. This exploration not only sheds light on the mathematical underpinnings of causal dynamical triangulations but also highlights its potential to offer new perspectives on the fabric of reality itself.

Key Findings and Future Directions for CDT

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality (Spectral Dimension) | Effective dimension of spacetime at different scales | ~4 at large scales, ~2 at Planck scale | Dimensionless |

| Number of Simplices | Count of fundamental building blocks (4-simplices) in triangulation | 10,000 – 100,000 | Count |

| Volume | Total spacetime volume represented by the triangulation | Varies by simulation setup | Number of 4-simplices |

| Time Slices | Number of discrete time steps in the triangulation | 20 – 100 | Count |

| Curvature | Average curvature derived from triangulation | Near zero (flat) to positive curvature | Dimensionless (normalized) |

| Phase Transition Points | Critical values of coupling constants where geometry changes phase | Depends on bare coupling constants (e.g., kappa_0, Delta) | Dimensionless |

| Hausdorff Dimension | Fractal dimension describing scaling of volume with radius | Approximately 4 at large scales | Dimensionless |

The Emergence of a Stable Four-Dimensional Spacetime

Perhaps the most compelling result from CDT is the robust emergence of a stable, dynamically generated four-dimensional spacetime. In many quantum gravity approaches, achieving a smooth, four-dimensional macroscopic spacetime is a significant challenge. CDT, by its very construction and through its simulations, demonstrates a mechanism by which such a spacetime can emerge from a collection of discrete building blocks. This provides a strong indication that CDT is on the right track towards a consistent theory of quantum gravity.

Implications for Cosmology and Black Holes

The findings of CDT have potentially profound implications for our understanding of the early universe and the nature of black holes. The emergence of a de Sitter phase, for example, offers a potential framework for understanding cosmic inflation, a period of rapid expansion thought to have occurred shortly after the Big Bang. Furthermore, CDT could provide insights into the quantum nature of black hole singularities, where the curvature of spacetime becomes infinite in classical general relativity.

Ongoing Research and Open Questions

Despite its successes, CDT is an active area of research with many open questions. One challenge lies in fully understanding the transition from the microscopic quantum regime to the macroscopic classical spacetime we observe. Precisely connecting the cosmological constant observed in our universe to the parameters used in CDT simulations remains an active area of investigation. Additionally, exploring the implications of CDT for other fundamental questions in physics, such as the nature of dark matter and dark energy, is an ongoing endeavor. The CDT approach, with its unique blend of discreteness, causality, and computational power, continues to offer a promising avenue for unraveling the mysteries of quantum gravity.

WATCH THIS 🔥 YOUR PAST STILL EXISTS — Physics Reveals the Shocking Truth About Time

FAQs

What is causal dynamical triangulations (CDT)?

Causal dynamical triangulations is a theoretical framework used in quantum gravity research. It aims to describe the quantum properties of spacetime by constructing it from simple building blocks called simplices, arranged in a way that respects causality.

How does CDT differ from other approaches to quantum gravity?

Unlike some other approaches, CDT imposes a strict causal structure on the triangulated spacetime, meaning that the arrangement of simplices respects the direction of time. This helps avoid certain problems like non-physical geometries and allows for a well-defined path integral formulation.

What are simplices in the context of CDT?

Simplices are the fundamental building blocks used in CDT to approximate spacetime. In two dimensions, a simplex is a triangle; in three dimensions, a tetrahedron; and in four dimensions, a 4-simplex. These are glued together in a way that preserves causality to model the geometry of spacetime.

What is the goal of using causal dynamical triangulations?

The primary goal of CDT is to provide a non-perturbative and background-independent formulation of quantum gravity. Researchers hope it will help unify general relativity and quantum mechanics by describing how spacetime behaves at the Planck scale.

Has CDT produced any significant results or predictions?

Yes, CDT has shown promising results, such as the emergence of a four-dimensional spacetime from the quantum superposition of geometries and indications of a phase structure that could correspond to different quantum gravitational regimes. These findings support the viability of CDT as a candidate theory of quantum gravity.