The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) stands as a profound relic of the early universe, a faint afterglow from a time when the cosmos transitioned from a dense, opaque plasma to a transparent, expanding expanse. Within this ancient light, scientists seek to decipher the very blueprint of cosmic structure, the subtle ripples and irregularities that, over billions of years, sculpted the vast tapestry of galaxies and clusters we observe today. These imperfections, known as primordial fluctuations, are not mere static blemishes; they are the seeds from which all complexity in the universe sprouted. This article endeavors to unveil the nature of these primordial fluctuations, exploring their origins, their observable signatures in the CMB, and the scientific tools and missions dedicated to their precise measurement.

Echoes of the Inflationary Epoch

The prevailing cosmological model, the Lambda-CDM model, suggests that the universe underwent a period of extremely rapid expansion shortly after the Big Bang, a phase known as cosmic inflation. Imagine the universe as a tiny, perfectly smooth, and infinitesimally small point. Inflation, like an incredibly powerful puff of air, stretched this point to an unfathomable size in a fraction of a second. This expansion was not perfectly uniform; it was subject to the inherent uncertainties of quantum mechanics.

Quantum Fluctuations as Seeds

At the quantum level, even seemingly empty space is a roiling sea of virtual particles popping into and out of existence. During inflation, these microscopic quantum fluctuations, which would typically average out to zero over time, were stretched to macroscopic scales. Think of it as picking up a perfectly smooth piece of fabric and then stretching it to the size of a continent – any tiny crinkles or bumps present in the original fabric would become significant features on the larger surface. These amplified quantum fluctuations became the primordial density variations that would later coalesce into matter.

The Specter of the Early Universe

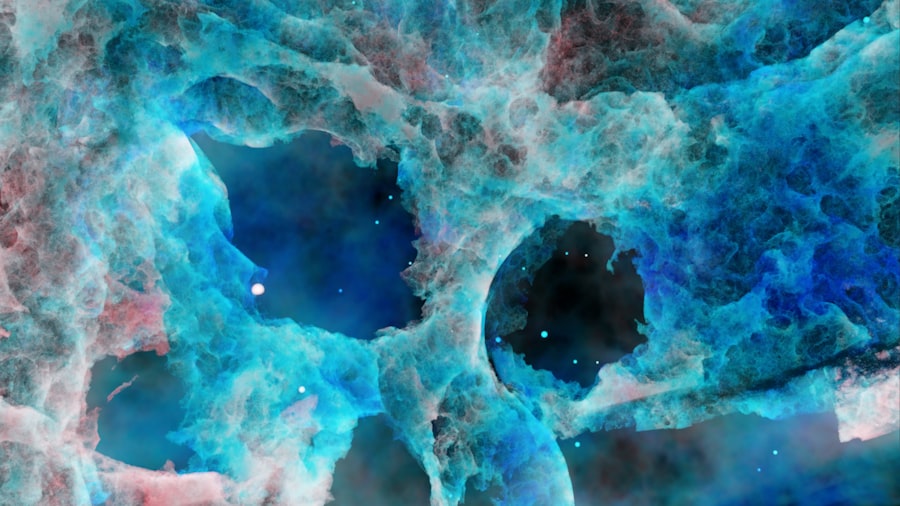

Prior to recombination, the epoch when the universe cooled enough for electrons and protons to form neutral atoms and allowing photons to travel freely, the universe was a dense, ionized plasma. In this state, photons were constantly scattering off charged particles, making the universe opaque, much like looking through a thick fog. Density variations within this plasma meant that some regions were slightly hotter or cooler, denser or less dense, than others. These variations dictated where photons would encounter more or less resistance to their propagation.

Primordial fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) provide crucial insights into the early universe’s conditions and the formation of large-scale structures. For a deeper understanding of this fascinating topic, you can explore a related article that delves into the implications of these fluctuations on our current cosmological models. To read more, visit this article.

Observable Signatures in the Cosmic Microwave Background

Temperature Anisotropies: The CMB’s Mottled Face

The most striking signature of primordial fluctuations in the CMB is its temperature distribution across the sky. While the CMB is remarkably uniform in temperature, averaging around 2.725 Kelvin, it is not perfectly so. Precise measurements reveal tiny temperature differences, on the order of parts per hundred thousand, across the celestial sphere. These variations are not random noise; they are a direct imprint of the density fluctuations that existed in the early universe. Regions that were slightly denser in the primordial plasma, due to the stretched quantum fluctuations, would have cooled more slowly and thus appear as warmer spots in the CMB. Conversely, less dense regions would have cooled faster, appearing as cooler spots. This “mottled” appearance of the CMB is akin to looking at a cooling ember – subtle variations in the glowing surface reveal underlying differences in its composition and heat distribution.

The Angular Power Spectrum: A Statistical Fingerprint

Scientists analyze these temperature anisotropies by decomposing them into their constituent angular scales. This statistical representation is known as the angular power spectrum. Imagine the CMB as a canvas painted with various sizes of spots. The angular power spectrum acts like a histogram, quantifying how much “power” or amplitude exists at each particular angular size of these spots. Peaks and troughs in the power spectrum are not arbitrary; they are directly linked to the physical processes that occurred in the early universe, including the characteristic scales imprinted by inflation and the subsequent acoustic oscillations.

Polarization: Unveiling the CMB’s Spin

Beyond temperature variations, the CMB also exhibits polarization. Polarization refers to the direction in which the electromagnetic waves of light are oscillating. The scattering of CMB photons off electrons in the early universe imprinted a specific pattern of polarization on the light. This polarization can be broadly categorized into two types: E-modes and B-modes. E-mode polarization is generated by density fluctuations and is thus a direct probe of primordial fluctuations. B-mode polarization, on the other hand, can be generated by primordial gravitational waves, which are another predicted consequence of inflation, or by gravitational lensing of E-modes. Detecting B-modes would be a monumental discovery, offering direct evidence of inflation and providing insights into the energy scale at which it occurred.

The Role of Acoustic Oscillations

Sound Waves in the Primordial Plasma

Before recombination, the early universe was a tightly coupled soup of photons, baryons (protons and neutrons), and dark matter. The photons acted as a driving force for pressure waves within this plasma. Imagine shouting in a confined space – the sound creates compressions and rarefactions, waves of high and low pressure. Similarly, slight overdensities in the primordial plasma led to regions of higher pressure, causing them to expand, while underdense regions became less pressurized. These pressure variations propagated as sound waves, or acoustic oscillations, through the plasma.

The Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO)

The peaks and troughs in the CMB’s angular power spectrum are a direct consequence of these acoustic oscillations. The most prominent peak, for instance, corresponds to the scale at which sound waves had traveled for the entire duration of the plasma phase, from the initial inflationary perturbation to the point of recombination. The other peaks and troughs reveal information about the amplitude of these oscillations at different stages of their propagation. These features are often referred to as Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO) because they are influenced by the baryonic matter.

The Influence of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

While acoustic oscillations are primarily driven by baryonic matter and photons, the presence of dark matter and dark energy also leaves its indelible mark. Dark matter, which interacts gravitationally but not electromagnetically, does not participate in the photon pressure-driven oscillations. This difference in behavior allows scientists to disentangle the contributions of baryonic matter and dark matter to the observed fluctuations. Dark energy, which is thought to be responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe, plays a more subtle role, primarily influencing the expansion history and thus the propagation of CMB light.

Scientific Missions and Observatories

Ground-Based Telescopes: Peering Through the Atmosphere

Several ground-based telescopes have been instrumental in measuring the CMB with increasing precision. The South Pole Telescope (SPT) and the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) are prime examples. Located at high, dry altitudes, they minimize atmospheric interference. These telescopes employ extremely sensitive microwave detectors to map minute temperature variations in the CMB across large swaths of the sky. Their observations have provided crucial data for refining cosmological parameters and testing the predictions of the Lambda-CDM model.

Satellite Observatories: A Bird’s Eye View

Space-based observatories offer an unparalleled vantage point, free from the distorting effects of Earth’s atmosphere. The Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite, launched in 1989, provided the first detailed map of CMB temperature anisotropies, confirming the blackbody spectrum of the CMB and revealing the existence of these subtle temperature variations. The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) followed, delivering higher resolution maps and significantly reducing uncertainties in key cosmological parameters. Most recently, the Planck satellite, operated by the European Space Agency, has provided the most precise and comprehensive CMB maps to date, offering unprecedentedly detailed information about the early universe and its primordial fluctuations.

The Quest for B-Modes: A New Frontier

The search for B-mode polarization in the CMB remains a highly active area of research and a major focus for future missions. Experiments like the BICEP/Keck Array and the forthcoming Simons Observatory and LiteBIRD are specifically designed to detect these elusive signals. The detection of primordial B-modes would be a game-changer, offering direct evidence for inflationary cosmology and potentially unlocking secrets about the very first moments of our universe.

Recent studies on primordial fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background have shed light on the early universe’s conditions and the formation of large-scale structures. These fluctuations, which are tiny variations in temperature and density, provide crucial insights into the fundamental physics of our universe. For a deeper understanding of this fascinating topic, you can explore a related article that discusses the implications of these fluctuations on cosmology and the evolution of galaxies. To read more about this, visit this insightful resource.

Implications for Cosmology and Fundamental Physics

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude of Fluctuations (ΔT/T) | Relative temperature variations in the CMB due to primordial fluctuations | ~10-5 | Dimensionless |

| Power Spectrum Peak Multipole (l) | Angular scale of the first acoustic peak in the CMB power spectrum | ~220 | Multipole moment (l) |

| Scalar Spectral Index (ns) | Describes the scale dependence of primordial fluctuations | ~0.96 – 0.97 | Dimensionless |

| Tensor-to-Scalar Ratio (r) | Ratio of primordial gravitational wave amplitude to density fluctuations | Dimensionless | |

| Correlation Length | Typical scale over which fluctuations are correlated | ~1° on the sky | Degrees |

| Temperature Anisotropy RMS | Root mean square of temperature fluctuations in the CMB | ~18 μK | Microkelvin (μK) |

Refining the Standard Cosmological Model

The precise measurement of primordial fluctuations in the CMB has been a cornerstone in establishing and refining the Lambda-CDM model. The amplitudes and scales of these fluctuations provide strong constraints on the relative abundances of dark matter, baryonic matter, and dark energy, as well as the geometry of the universe and its expansion rate. Without the information gleaned from the CMB, our understanding of these fundamental cosmological parameters would be far less certain.

Testing Theories of Inflation

Primordial fluctuations are the direct consequence of inflationary theory. The specific characteristics of these fluctuations, such as their statistical distribution and their correlation with gravitational waves (which would produce B-modes), serve as critical tests for different inflationary models. The absence of certain predicted features or the discovery of unexpected patterns could lead to the modification or rejection of existing inflationary scenarios and inspire new theoretical frameworks.

Probing the Physics of the Very Early Universe

The CMB acts as a window into a realm of physics that is otherwise inaccessible to direct observation. The energy scales involved in inflation are thought to be far beyond the reach of any terrestrial particle accelerator. The imprints left on the CMB by these extreme conditions provide invaluable clues about the fundamental forces and particles that governed the universe at its inception. Understanding primordial fluctuations is thus intertwined with understanding the deepest mysteries of quantum gravity and the very nature of reality at its most fundamental level. The CMB, in essence, is the universe’s ancient photograph, and within its developing image, we are learning to read the story of its birth.

FAQs

What are primordial fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background?

Primordial fluctuations are tiny variations in the density and temperature of matter and radiation in the early universe. These fluctuations are imprinted on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation and serve as the seeds for the formation of galaxies and large-scale structures in the universe.

How are primordial fluctuations detected in the cosmic microwave background?

Primordial fluctuations are detected by measuring the temperature and polarization variations in the CMB using sensitive instruments on satellites, balloons, and ground-based telescopes. These measurements reveal a pattern of hot and cold spots that correspond to the density fluctuations present shortly after the Big Bang.

Why are primordial fluctuations important for cosmology?

Primordial fluctuations provide critical information about the early universe’s conditions and the physics of the Big Bang. They help scientists understand the origin of structure in the universe, test theories of cosmic inflation, and determine key cosmological parameters such as the universe’s composition, age, and rate of expansion.

What causes primordial fluctuations in the early universe?

Primordial fluctuations are believed to originate from quantum fluctuations during the inflationary period, a rapid expansion phase in the very early universe. These quantum fluctuations were stretched to macroscopic scales, creating the initial irregularities in matter density that later evolved into galaxies and clusters.

How do primordial fluctuations affect the large-scale structure of the universe?

The small density variations from primordial fluctuations grew over billions of years due to gravitational attraction, leading to the formation of stars, galaxies, and galaxy clusters. The distribution and characteristics of these structures observed today reflect the pattern of the original fluctuations seen in the CMB.