The early universe, a period of profound physical transformation, presents a unique laboratory for understanding fundamental cosmic constants and principles, among them the speed of light. This article explores the intricate dance between these nascent cosmic conditions and the seemingly immutable speed limit of the universe.

The universe’s earliest moments were characterized by extreme conditions, far removed from the cold, expansive cosmos observed today. This period, often referred to as the cosmic dawn, encompasses several distinct epochs, each with its own defining physical phenomena.

The Planck Epoch (t < $10^{-43}$ seconds)

The Planck epoch represents the absolute theoretical limit of current physics. During this infinitesimal timeframe, all four fundamental forces—gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces—are believed to have been unified into a single superforce.

- Quantum Gravity’s Reign: Within this epoch, the fabric of spacetime itself is thought to have been subject to quantum fluctuations, a realm where our classical understanding of gravity breaks down. Theoretical frameworks like string theory and loop quantum gravity attempt to describe this elusive era.

- The Unification Hypothesis: The concept of a grand unified theory (GUT) posits that at sufficiently high energies, the fundamental forces converge. The Planck epoch is the ultimate arena for such unification.

The Grand Unification Epoch ($10^{-43}$ to $10^{-36}$ seconds)

Following the Planck epoch, gravity separated from the other three forces, which remained unified as the electronuclear force. This period witnessed the universe expanding and cooling, though it remained extraordinarily hot and dense.

- Emergence of Fundamental Particles: As the universe continued to cool, the extreme energies allowed for the creation and annihilation of vast numbers of exotic, massive particles. Quarks, leptons, and their antiparticles dominated the cosmic soup.

- Symmetry Breaking: The separation of forces during this epoch is an example of symmetry breaking, a crucial concept in particle physics where a system transitions from a higher, more symmetric state to a lower, less symmetric one.

The Inflationary Epoch ($10^{-36}$ to $10^{-32}$ seconds)

One of the most significant theoretical developments in cosmology is the inflationary epoch, a period of exponential expansion immediately following the grand unification epoch. This rapid expansion addresses several long-standing cosmological puzzles.

- Solving Cosmological Puzzles: Inflation elegantly explains the flatness problem (why the universe appears spatially flat), the horizon problem (why disparate regions of the universe appear causally connected), and the monopole problem (the predicted overabundance of magnetic monopoles).

- The Inflaton Field: Inflation is theorized to be driven by a hypothetical scalar field known as the inflaton field. As this field slowly “rolled down” its potential energy landscape, it imparted a tremendous repulsive force, causing spacetime to expand at an astonishing rate.

In exploring the fascinating realm of early universe physics, one cannot overlook the implications of the speed of light on our understanding of cosmic evolution. A related article that delves into this topic is available at My Cosmic Ventures, where it discusses how the finite speed of light influences our observations of distant galaxies and the formation of the universe shortly after the Big Bang. This intersection of light speed and cosmic history provides crucial insights into the fundamental laws governing our universe.

The Limitless Speed of Light: A Universal Constant

The speed of light in a vacuum, denoted as ‘c’, is a fundamental physical constant with a value of approximately $299,792,458$ meters per second. Its role in the early universe, where spacetime itself was undergoing dramatic transformations, is a subject of intense scrutiny.

Einstein’s Postulate and Its Implications

Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity, developed in the early 20th century, established the speed of light as a cosmic speed limit, immutable for all inertial observers. This postulate has profound implications for our understanding of spacetime, mass, and energy.

- The Fabric of Spacetime: Relativity demonstrated that space and time are not independent entities but are interwoven into a single four-dimensional continuum: spacetime. The speed of light acts as the fundamental connection between these dimensions.

- Mass-Energy Equivalence: The iconic equation $E=mc^2$ directly links mass and energy through the square of the speed of light, illustrating its central role in the fundamental constituents of the universe.

The Early Universe and ‘c’

While the value of ‘c’ is constant in any given local inertial frame, its global implications within an expanding, evolving universe warrant detailed consideration. The expansion of space itself does not imply that objects are moving through space faster than light; rather, the “space” between objects is stretching.

- Cosmological Redshift: The observation of distant galaxies receding from us, and the associated redshift of their light, is a direct consequence of the expansion of space. This does not mean these galaxies are traveling through space faster than light, but rather that the light waves are stretched as space itself expands.

- Horizon Problem Revisited: The horizon problem, addressed by inflation, highlights the apparent paradox of causally disconnected regions of the early universe having the same temperature. If light defined the maximum speed of information transfer, how could these regions have exchanged information to reach thermal equilibrium? Inflation offers a solution by proposing that these regions were once causally connected before the rapid expansion separated them.

Variable Speed of Light (VSL) Theories

Despite the foundational nature of ‘c’ as a constant, some theoretical frameworks propose that the speed of light might not have always been constant, particularly in the extreme conditions of the very early universe. These “variable speed of light” (VSL) theories attempt to address cosmological puzzles without invoking inflation or offer alternative explanations for observed phenomena.

Motivations for VSL Theories

VSL theories emerged as an attempt to solve some of the same cosmological problems that inflation addresses, such as the horizon and flatness problems, often without the need for an inflaton field.

- Addressing the Horizon Problem: If the speed of light were much higher in the very early universe, causally disconnected regions could have exchanged information and homogenized their temperatures, thus solving the horizon problem.

- Alternative to Inflation: Some VSL models provide an alternative mechanism for solving cosmological puzzles, potentially offering a different pathway to the universe we observe today.

Mechanisms and Challenges

VSL theories typically involve modifying fundamental constants or introducing new fields that influence the propagation of light. However, these models face significant theoretical and observational challenges.

- Modifying Fundamental Constants: VSL theories often propose that fundamental constants, including ‘c’, were not truly constant but varied with energy density or cosmic time. This concept challenges the bedrock of modern physics.

- Lorentz Invariance: A major hurdle for VSL theories is maintaining Lorentz invariance, a fundamental principle of special relativity stating that the laws of physics are the same for all inertial observers. Modifying ‘c’ generally implies a violation of this principle.

- Observational Constraints: Current observational data, including precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background and distant supernovae, place stringent constraints on any proposed variation of fundamental constants. No compelling evidence unequivocally supports a variable speed of light.

The Quantum Nature of Spacetime and Light Propagation

The intersection of quantum mechanics and general relativity, particularly in the nascent universe, raises profound questions about the nature of spacetime and the propagation of light.

Quantum Fluctuations and Foamy Spacetime

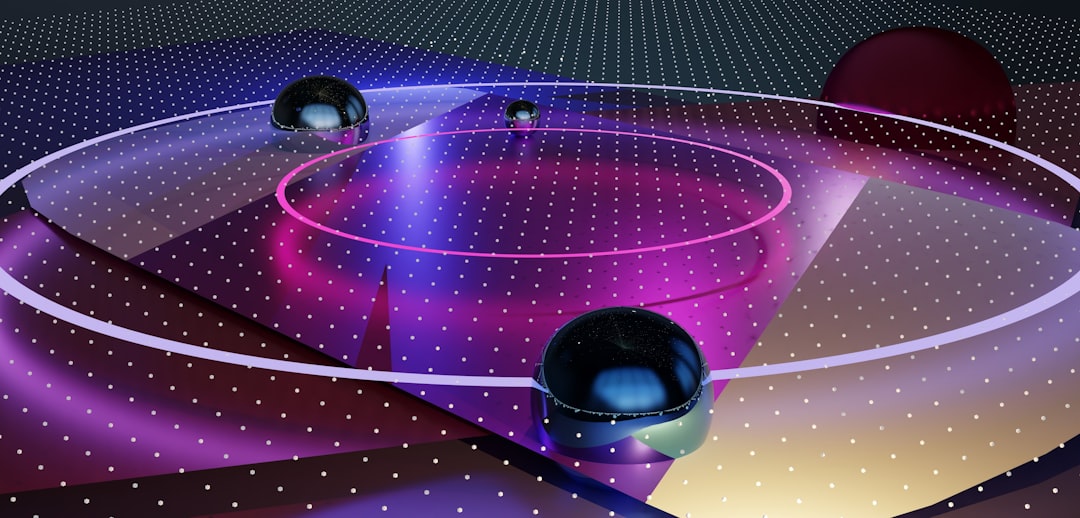

At the Planck scale, spacetime is not expected to be smooth and continuous, but rather a “quantum foam,” characterized by constant fluctuations in its geometry. This tumultuous environment could have unforeseen effects on light.

- Non-Commutative Geometry: Some theories suggest that at these extreme scales, spacetime itself might exhibit non-commutative properties, meaning the order in which measurements are made impacts the outcome. This could subtly alter the paths of photons.

- Gravitons and the Fabric of Spacetime: In a quantum theory of gravity, spacetime would be quantized, with gravitons mediating gravitational interactions. The interactions of photons with these hypothetical gravitons could lead to deviations from classical light propagation.

Loop Quantum Gravity and String Theory’s Perspectives

Theoretical frameworks attempting to unify quantum mechanics and gravity offer different perspectives on the propagation of light in the early universe.

- Discretized Spacetime in Loop Quantum Gravity: Loop quantum gravity posits that spacetime is not continuous but is composed of discrete “loops” or “atoms” of spacetime. This granular structure could, in principle, lead to phenomena such as energy-dependent speed of light.

- Extra Dimensions in String Theory: String theory suggests the existence of extra spatial dimensions beyond the familiar three. If these dimensions were compactified at incredibly small scales in the early universe, their geometry could have influenced the propagation of light.

In exploring the fascinating realm of early universe physics, one cannot overlook the critical role that the speed of light plays in our understanding of cosmic events. A related article that delves into these concepts can be found on My Cosmic Ventures, where it discusses how the limitations imposed by light speed influence our observations of the universe’s infancy. For those interested in this captivating topic, you can read more about it in the article here.

The Enduring Mystery of ‘c’ in the Early Cosmos

| Metric | Value | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed of Light (c) | 299,792,458 | m/s | Fundamental constant representing the speed of light in vacuum |

| Age of the Universe at Recombination | 380,000 | years | Time when the universe became transparent to light |

| Temperature at Recombination | 3000 | K | Approximate temperature when electrons combined with protons to form neutral hydrogen |

| Hubble Parameter at Recombination | 1.8 x 10^5 | km/s/Mpc | Expansion rate of the universe at recombination epoch |

| Particle Horizon Distance (Early Universe) | ~280,000 | light years | Maximum distance light could have traveled since the Big Bang at recombination |

| Planck Time | 5.39 x 10^-44 | seconds | Earliest meaningful time after the Big Bang where physics as known applies |

| Speed of Sound in Early Universe Plasma | ~173,000 | km/s | Speed of acoustic waves in the photon-baryon fluid before recombination |

While the concept of a constant speed of light, ‘c’, is a cornerstone of modern physics, its behavior and implications in the extreme conditions of the early universe continue to be a fertile ground for theoretical exploration and observational scrutiny.

Ongoing Research and Future Observational Avenues

Cosmologists and physicists continue to investigate the nature of ‘c’ and other fundamental constants, seeking ever more precise measurements and theoretical refinements.

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Polarization: Detailed studies of the polarization of the CMB can provide insights into fundamental physics in the very early universe, potentially constraining models that predict variations in fundamental constants.

- Gravitational Wave Astronomy: The burgeoning field of gravitational wave astronomy offers a new window into the early universe. Gravitational waves, as ripples in spacetime, travel at the speed of light. Any discrepancy between the speed of gravitational waves and electromagnetic waves would have profound implications for our understanding of ‘c’ and the structure of spacetime.

- Precision Spectroscopy of Distant Quasars: Analyzing the spectral lines from distant quasars allows physicists to test for potential variations in fundamental constants over cosmic time. Small shifts in these lines could indicate changes in the fine-structure constant or other parameters linked to ‘c’.

The Interplay of Theory and Observation

The exploration of the early universe, and the role of the speed of light within it, exemplifies the symbiotic relationship between theoretical physics and observational astronomy. Theoretical models propose explanations for observed phenomena and predict new ones, while observational data, in turn, constrains or supports these theories. The seemingly immutable speed of light, while a constant in our everyday experience, serves as a beacon guiding our understanding of the universe’s most enigmatic and profound beginnings. The quest to fully comprehend ‘c’ in the cosmic dawn is, in essence, the quest to understand the very fabric of reality.

FAQs

What is meant by the “early universe” in physics?

The “early universe” refers to the period shortly after the Big Bang, typically within the first few minutes to hundreds of thousands of years, when the universe was extremely hot, dense, and rapidly expanding. During this time, fundamental particles and forces began to form, setting the stage for the development of stars, galaxies, and the large-scale structure of the cosmos.

How does the speed of light relate to early universe physics?

The speed of light (approximately 299,792 kilometers per second) is a fundamental constant in physics and plays a crucial role in early universe models. It determines how fast information and energy can travel, influencing the rate of expansion, the propagation of radiation, and the formation of cosmic structures during the universe’s infancy.

Did the speed of light change during the early universe?

Current scientific consensus holds that the speed of light has remained constant since the early universe. However, some theoretical models have explored the possibility of a varying speed of light in the very early moments after the Big Bang to address certain cosmological puzzles, but these ideas remain speculative and are not widely accepted.

Why is understanding the early universe important for physics?

Studying the early universe helps physicists understand the fundamental laws of nature, the origin of matter and energy, and the evolution of the cosmos. It provides insights into particle physics, cosmology, and the unification of forces, helping to answer profound questions about the origin and fate of the universe.

What tools do scientists use to study early universe physics and the speed of light?

Scientists use a combination of observational data from telescopes (such as the cosmic microwave background radiation measurements), particle accelerators, and theoretical models based on general relativity and quantum mechanics. These tools help them reconstruct conditions of the early universe and test the constancy of the speed of light over cosmic time.