Einstein’s spacetime, a concept fundamental to modern physics, revolutionized our understanding of the universe. Before Einstein, space and time were considered separate, absolute entities, like immutable stages upon which events unfolded. However, Albert Einstein, through his theories of special and general relativity, demonstrated that space and time are not independent but are interwoven into a single continuum: spacetime. This article provides a brief introduction to this complex notion, aiming to illuminate its core principles without delving into overly technical jargon.

Before the advent of Einstein’s theories, the prevailing view of the cosmos was largely Newtonian. Isaac Newton, in his seminal work Principia Mathematica, posited an absolute space and absolute time. You can learn more about managing your schedule effectively by watching this block time tutorial.

Absolute Space: The Unchanging Stage

Newton envisioned space as a fixed, three-dimensional grid, a passive backdrop against which all physical phenomena occurred. This ‘absolute space’ was believed to be infinite and unchanging, unaffected by the matter or events within it. Imagine a perfectly rigid, transparent box that extends infinitely in all directions. All objects exist and move within this box, but the box itself remains the same, regardless of what happens inside. This was the fundamental understanding of space for centuries.

Absolute Time: The Universal Clock

Similarly, Newton proposed absolute time, a concept implying that time flows at a uniform rate for all observers, everywhere in the universe. This meant that a second measured by an observer on Earth would be identical to a second measured by an observer on Mars, or any other celestial body. Time was seen as a universal river, flowing ceaselessly and identically for everyone. There was no suggestion that an observer’s motion or gravitational influence could alter the passage of time.

The Inertial Frame of Reference

Within this Newtonian framework, the concept of an inertial frame of reference was crucial. An inertial frame is a coordinate system where an object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion continues in motion with constant velocity, unless acted upon by a force. Newton’s laws of motion were derived within these inertial frames. The idea was that these frames were somehow “privileged,” but they were understood as existing within the absolute space and time.

Einstein’s theory of relativity revolutionized our understanding of spacetime, fundamentally altering the way we perceive the universe. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article can be found at My Cosmic Ventures, which delves into the implications of spacetime on modern physics and its applications in various scientific fields. This resource provides valuable insights into how relativity continues to shape our understanding of the cosmos.

Special Relativity: The Intertwining of Space and Time

Einstein’s special theory of relativity, published in 1905, marked a profound departure from Newtonian physics. It is built upon two fundamental postulates:

Postulate 1: The Principle of Relativity

The laws of physics are the same for all observers in uniform motion (inertial frames of reference). This extends Galileo’s principle of relativity from mechanics to all laws of physics, including electromagnetism. This means that regardless of your constant velocity, the fundamental laws governing the universe will behave in the same way for you as they do for someone moving at a different constant velocity. There is no absolute, stationary frame of reference in the universe; all inertial frames are equally valid.

Postulate 2: The Constancy of the Speed of Light

The speed of light in a vacuum, denoted by ‘c,’ is the same for all inertial observers, regardless of the motion of the light source or the observer. This is perhaps the most counter-intuitive postulate of special relativity. Imagine throwing a ball from a moving car. An observer on the ground would see the ball moving at the speed of the car plus the speed at which the ball was thrown. However, light does not behave this way. If you shine a flashlight from a spaceship moving at near light speed, an observer on Earth will still measure the light from that flashlight to be traveling at ‘c,’ not ‘c’ plus the speed of the spaceship. This constancy of light speed has remarkable consequences.

Time Dilation: Time is Not Absolute

One of the most striking consequences of special relativity is time dilation. If two observers are in relative motion, time will pass at different rates for them. For the observer moving at a higher velocity, time will appear to pass more slowly compared to the observer who is relatively at rest. This is often illustrated by the “twin paradox.” Imagine two identical twins. One twin stays on Earth, while the other travels on a spaceship at near the speed of light, journeys to a distant star, and returns. Upon the traveler twin’s return, they will be younger than the Earthbound twin. This is not an illusion; it’s a real physical effect. The faster you move through space, the slower you move through time. Think of it as having a fixed budget for “movement” through spacetime. The more you spend on moving through space, the less you have left for moving through time.

Length Contraction: Space is Not Absolute

Another consequence is length contraction. Objects moving at relativistic speeds appear shorter in the direction of their motion when observed by a stationary observer. If the twin in the spaceship were to measure the length of their spaceship while it was in motion, they would find it to be its normal length. However, to the twin on Earth, the spaceship would appear to be shorter in its length of travel. This effect is also a direct consequence of the constancy of the speed of light and the interconnectedness of space and time.

The Invariant Interval: Spacetime’s True Nature

Special relativity reveals that while space and time are relative to the observer, there is a quantity that remains invariant: the spacetime interval. This interval combines measurements of space and time in a specific way. It’s like a fundamental “distance” in spacetime that all observers will agree upon, even if they disagree on the individual spatial and temporal components. This invariant interval is the bedrock upon which the concept of spacetime is built.

General Relativity: Gravity as Spacetime Curvature

Ten years after special relativity, Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915. This theory extended his ideas to include gravity, presenting it not as a force pulling objects together, but as a manifestation of the curvature of spacetime.

Revisiting Gravity: A Departure from Newton

Newton described gravity as a force acting instantaneously across vast distances. This action-at-a-distance concept troubled Einstein, as it seemed incompatible with the finite speed of light. General relativity offers a new perspective: gravity is not a force, but a geometric property of spacetime itself.

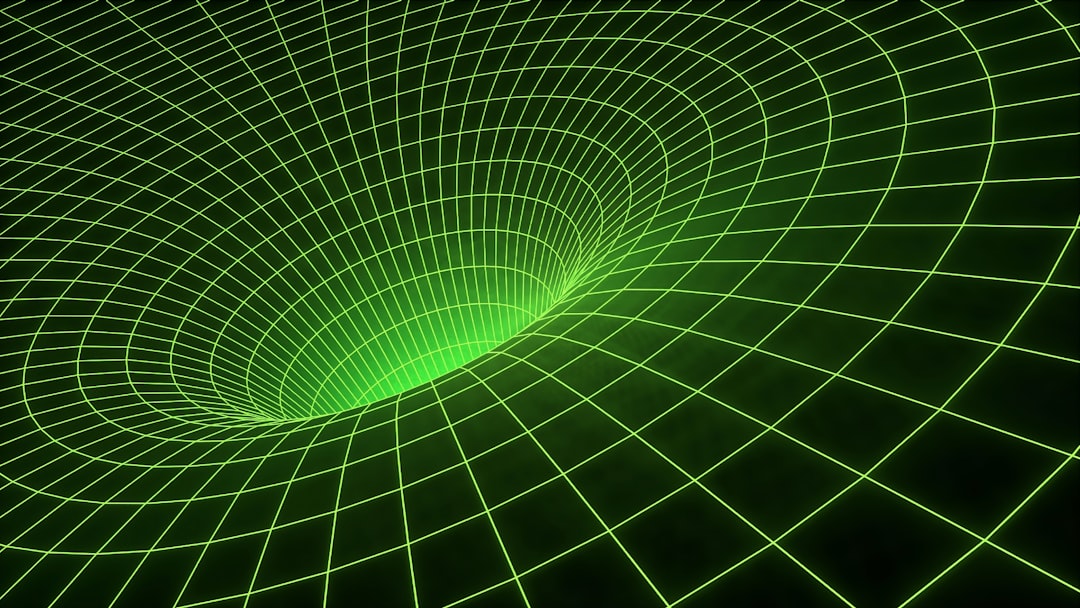

Spacetime as a Fabric

Imagine spacetime as a vast, flexible sheet or fabric. Objects with mass and energy warp this fabric, creating curves and dips. This curvature is what we perceive as gravity. A massive object, like the Sun, creates a significant warp in the spacetime fabric around it. Planets, moons, and other celestial bodies then follow these curves, not because they are being pulled by a force, but because they are moving along the most direct path in the curved spacetime. Think of a bowling ball placed on a stretched rubber sheet. The bowling ball creates a depression. If you roll a marble near the bowling ball, the marble will curve towards it, following the contour of the sheet. This is analogous to how planets orbit stars.

Einstein Field Equations: The Mathematical Description

The relationship between the distribution of mass and energy and the curvature of spacetime is described by the Einstein field equations. These are a set of ten non-linear partial differential equations that are remarkably complex. They essentially state that the geometry of spacetime is determined by the matter and energy contained within it. In essence, matter tells spacetime how to curve, and curved spacetime tells matter how to move.

Gravitational Lensing: Light Bending in Curved Spacetime

One of the most compelling predictions of general relativity is gravitational lensing. Because light travels through spacetime, and spacetime can be curved, light itself can be bent by massive objects. When light from a distant star or galaxy passes by a massive object, such as another galaxy or a galaxy cluster, its path is deflected. This can cause the light to bend around the massive object, acting like a lens and producing distorted, magnified, or multiple images of the distant object. This phenomenon has been experimentally verified and serves as strong evidence for Einstein’s theory.

Gravitational Waves: Ripples in the Spacetime Fabric

Another significant prediction of general relativity is the existence of gravitational waves. These are ripples in the fabric of spacetime that propagate at the speed of light. They are generated by extremely energetic cosmic events, such as the merger of black holes or neutron stars. Imagine plucking a string on a guitar; it vibrates and creates sound waves. Similarly, cataclysmic cosmic events can “pluck” the fabric of spacetime, sending out gravitational waves. These waves were directly detected for the first time in 2015 by the LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) collaboration, a landmark achievement in physics.

The Unified Four-Dimensional Continuum

Spacetime is typically represented as a four-dimensional manifold, with three spatial dimensions and one temporal dimension. This unification is not merely an abstract mathematical concept; it has profound implications for how we understand the universe.

The Minkowski Spacetime: A Flat Background

Early within special relativity, Hermann Minkowski developed a geometrical framework for spacetime. He demonstrated that space and time could be unified into a single, four-dimensional entity. In the absence of gravity, spacetime can be visualized as being “flat,” much like a Euclidean plane. In this flat spacetime, the relationships between events are governed by the geometry of special relativity. Think of it as a perfectly flat, unwarped stage.

Events: Points in Spacetime

In spacetime, an “event” is a point defined by both its location in space and the instant in time it occurs. For example, a person eating breakfast at a specific location on Earth at a specific time is an event. If two observers are moving relative to each other, they will assign different spatial and temporal coordinates to the same event. However, as discussed earlier, they will agree on the spacetime interval between events. Every occurrence in the universe, from the smallest atomic interaction to the formation of galaxies, can be considered an event within the spacetime continuum.

Worldlines: Paths Through Spacetime

The path of an object or a particle through spacetime is called its worldline. A stationary object has a worldline that moves purely along the time dimension. A moving object has a worldline that traces a path through both space and time. For example, if you are sitting still, your worldline is a straight vertical line on a spacetime diagram (with time on the vertical axis and a spatial dimension on the horizontal). If you start walking, your worldline will begin to angle across the diagram, indicating your movement through space as time progresses.

Einstein’s theory of relativity revolutionized our understanding of spacetime, intertwining the fabric of space and time in ways that continue to influence modern physics. For those interested in exploring this concept further, a related article can be found at My Cosmic Ventures, which delves into the implications of spacetime on our perception of the universe. This resource provides valuable insights into how relativity shapes our understanding of gravity and the movement of celestial bodies, making it a fascinating read for anyone intrigued by the mysteries of the cosmos.

Implications and Further Exploration

| Concept | Description | Key Metric/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of Light (c) | Constant speed at which light travels in vacuum | 299,792,458 meters per second |

| Time Dilation | Time runs slower for an object moving close to the speed of light relative to a stationary observer | Δt’ = Δt / √(1 – v²/c²) |

| Length Contraction | Objects moving at relativistic speeds contract in the direction of motion | L’ = L √(1 – v²/c²) |

| Spacetime Interval (s²) | Invariant quantity combining space and time separations between events | s² = c²Δt² – Δx² – Δy² – Δz² |

| Mass-Energy Equivalence | Mass can be converted into energy and vice versa | E = mc² |

| Gravitational Time Dilation | Time runs slower in stronger gravitational fields | Δt’ = Δt √(1 – 2GM/rc²) |

| Schwarzschild Radius | Radius defining the event horizon of a non-rotating black hole | r_s = 2GM/c² |

The concept of spacetime has far-reaching implications and continues to be a cornerstone of modern physics. It forms the basis for our understanding of cosmology, black holes, and the very evolution of the universe.

Cosmology: The Universe on a Grand Scale

General relativity, with its concept of curved spacetime, provides the framework for understanding the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe. The discovery of the expansion of the universe, for instance, relies on solutions to the Einstein field equations. The universe is not a static stage with events happening within it; rather, spacetime itself is dynamic and evolving. The distances between galaxies are increasing, not because galaxies are moving through space, but because the space between them is expanding.

Black Holes: Regions of Extreme Spacetime Curvature

Black holes are perhaps the most dramatic manifestations of spacetime distortion predicted by general relativity. They are regions where gravity is so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape. At the heart of a black hole is a singularity, a point of infinite density where our current understanding of physics breaks down. The event horizon of a black hole is the boundary beyond which escape is impossible. It is in these extreme environments that the curvature of spacetime becomes profound.

The Quest for Quantum Gravity

While general relativity offers a magnificent description of gravity and spacetime on large scales, it does not fully reconcile with quantum mechanics, the theory that governs the realm of the very small. Physicists are actively pursuing a theory of quantum gravity, which would unify these two pillars of modern physics and provide a more complete understanding of phenomena like the formation of the universe at the Big Bang and the nature of black hole singularities. String theory and loop quantum gravity are prominent examples of such attempts.

Understanding Einstein’s spacetime is a journey into the fundamental nature of reality. It teaches us that space and time are not merely a passive backdrop but are active, interwoven participants in the cosmic drama, shaped by the presence of matter and energy. This introduction serves as a stepping stone for further exploration into the fascinating world of relativity and its profound impact on our understanding of the universe.

WATCH THIS 🔥 YOUR PAST STILL EXISTS — Physics Reveals the Shocking Truth About Time

FAQs

What is Einstein’s theory of relativity?

Einstein’s theory of relativity consists of two main parts: special relativity and general relativity. Special relativity, introduced in 1905, deals with the physics of objects moving at constant speeds, particularly close to the speed of light. General relativity, published in 1915, is a theory of gravitation that describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy.

What is spacetime in the context of relativity?

Spacetime is a four-dimensional continuum that combines the three dimensions of space with the dimension of time into a single interwoven framework. In Einstein’s relativity, events are described in terms of their position in both space and time, and the geometry of spacetime is affected by the presence of mass and energy.

How does general relativity explain gravity?

General relativity explains gravity not as a force but as the effect of curved spacetime. Massive objects like stars and planets cause spacetime to curve around them, and this curvature directs the motion of other objects, which move along the curved paths called geodesics. This explains phenomena such as the orbit of planets and the bending of light near massive bodies.

What are some key predictions of Einstein’s relativity related to spacetime?

Key predictions include time dilation (time runs slower near massive objects or at high speeds), length contraction (objects contract in the direction of motion at high speeds), gravitational lensing (light bends around massive objects), and the existence of black holes (regions where spacetime curvature becomes extreme). Many of these predictions have been confirmed by experiments and observations.

Why is Einstein’s concept of spacetime important in modern physics?

Einstein’s concept of spacetime revolutionized our understanding of the universe by unifying space and time and providing a new framework for gravity. It is fundamental to modern physics, underpinning cosmology, astrophysics, and technologies like GPS, which must account for relativistic effects to maintain accuracy.