The early universe, a realm of extreme densities and temperatures, remains shrouded in many mysteries. Among the most intriguing are primordial black holes (PBHs), hypothetical objects formed not from the collapse of massive stars, but from density fluctuations in the universe’s nascent stages. These cosmic relics offer a unique window into fundamental physics, cosmology, and the very origin of structures we observe today. Understanding PBHs is akin to decoding a cosmic fossil record, providing insights into an era long past and inaccessible to direct observation.

The standard model of cosmology, the Lambda-CDM model, describes the universe’s evolution from the Big Bang. In the earliest moments, the universe was a superheated, nearly homogeneous plasma. However, quantum fluctuations, tiny ripples in the fabric of spacetime, are thought to have been present. While most of these fluctuations smoothed out as the universe expanded, exceptionally large overdensities could have collapsed under their own gravity to form black holes. This process is distinct from the stellar collapse mechanisms that form astrophysical black holes in the present-day universe.

Inflationary Era Fluctuations

The leading paradigm for explaining these initial density perturbations is cosmic inflation. During an unimaginably brief period after the Big Bang, the universe underwent an exponential expansion, stretching microscopic quantum fluctuations to macroscopic scales. If the spectrum of these primordial fluctuations was not perfectly scale-invariant, or if there were specific features in the inflationary potential, certain regions could have become significantly overdense. Imagine a perfectly smooth sheet, but with tiny, almost imperceptible wrinkles. Inflation acts like a cosmic iron, but instead of smoothing them, it stretches some of these wrinkles into mountains and valleys.

Gravitational Collapse in the Radiation-Dominated Era

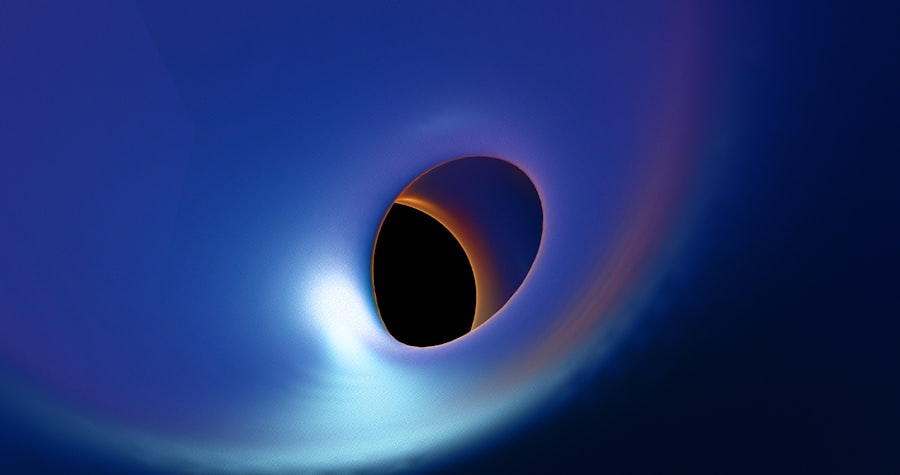

Following inflation, the universe entered a radiation-dominated era, where its energy density was primarily in the form of relativistic particles. During this phase, if a region’s overdensity exceeded a critical threshold (typically around $\delta \rho / \rho \gtrsim 0.1$), the gravitational pull inwards would overcome the outward pressure from radiation and expansion. These regions would then decouple from the cosmic expansion and collapse to form black holes. The mass of these PBHs would depend on the size of the horizon at the time of their formation, which itself depends on the formation epoch. Unlike stellar black holes, which have a minimum mass determined by the Chandrasekhar limit, PBHs could theoretically span an enormous range of masses, from Planck mass ($\sim 10^{-5}$ grams) up to hundreds of thousands of solar masses or even more.

Mass Scales and Formation Epochs

The formation time of a PBH is directly linked to its mass. Smaller PBHs would have formed earlier when the universe was denser and hotter, and the horizon scale was smaller. For instance, a PBH of around $10^{15}$ grams (roughly the mass of a small asteroid) would have formed within the first second after the Big Bang. Larger PBHs, perhaps several solar masses, would have formed much later, possibly during the quark-hadron transition or even the epoch of electroweak symmetry breaking. This relationship between mass and formation epoch makes PBHs a powerful probe of the early universe’s conditions at various critical junctures.

Recent studies on primordial black holes have sparked significant interest in the scientific community, particularly regarding their formation in the early universe. An insightful article discussing the implications of these black holes can be found at My Cosmic Ventures. This piece delves into the potential role of primordial black holes in cosmic evolution and their connection to dark matter, providing a comprehensive overview of current theories and research findings.

PBHs as Dark Matter Candidates

One of the most compelling reasons for studying primordial black holes is their potential role as a component, or even the entirety, of dark matter. Dark matter, an enigmatic substance that makes up about 27% of the universe’s mass-energy budget, interacts gravitationally but not electromagnetically, making it invisible to telescopes. If PBHs exist and have masses within certain ranges, they could fit this description perfectly.

Mass Windows for Dark Matter

Not all possible PBH mass ranges are viable candidates for dark matter. Observational constraints from various astrophysical phenomena severely restrict the allowed mass windows.

- Evaporating PBHs: PBHs with masses below about $10^{15}$ grams are predicted to evaporate via Hawking radiation within the age of the universe. If such light PBHs were a significant component of dark matter, their evaporation would produce observable gamma-ray backgrounds, which have not been detected at the predicted levels. This rules out PBHs in this mass range as the dominant dark matter component. Imagine tiny cosmic embers slowly burning out over billions of years, each emitting a faint glow as it disappears. We haven’t seen the cumulative glow of enough such embers to account for dark matter.

- Microlensing Constraints: For PBHs in the mass range of roughly $10^{-7}$ to $10^{2}$ solar masses, gravitational microlensing experiments (like MACHO and EROS) have set stringent limits. Microlensing occurs when a compact object passes in front of a distant star, temporarily brightening the star due to gravitational focusing of its light. The absence of a large number of such events suggests that PBHs in this range do not constitute a significant fraction of dark matter. This is like looking for tiny smudges on a distant lens; if there were enough of them, they would distort the light noticeably.

- Dynamical Constraints: Extremely massive PBHs (greater than a few hundred solar masses) are constrained by their potential effects on stellar clusters, dwarf galaxies, and the cosmic microwave background. For instance, the presence of many massive black holes could perturb wide binary star systems or heat up dwarf galaxies beyond what is observed.

Remaining Open Mass Windows

Despite these constraints, a few mass windows remain open for PBHs to be a substantial component of dark matter:

- Asteroid-Mass PBHs: The most robust window lies around $10^{17}$ to $10^{23}$ grams (roughly asteroid to lunar mass). These PBHs are too heavy to evaporate within the age of the universe but are too light to be efficiently detected by current microlensing surveys optimized for stellar-mass objects. Furthermore, their individual gravitational influence is too subtle to cause strong dynamical effects on large scales.

- Sub-solar mass to tens of solar masses: While microlensing constrains this range strongly, there are still some model-dependent loopholes or uncertainties that could allow for a small fraction of dark matter to be in this form.

- Very Massive PBHs (VMBHs): PBHs in the range of $10^2$ to $10^5$ solar masses, while heavily constrained, might still contribute a small fraction of dark matter, and could potentially serve as seeds for supermassive black holes.

The possibility of PBHs as dark matter compels a thorough exploration of these uncharted territories of mass and abundance. Their absence or presence would profoundly impact our understanding of the universe’s inventory.

PBHs as Seeds for Supermassive Black Holes

One of the most persistent puzzles in astrophysics is the existence of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) with masses exceeding a billion solar masses, observed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. How did these behemoths grow so quickly? Stellar black holes, formed from the collapse of early stars, would need an unrealistically efficient and rapid accretion process to reach such masses in such a short cosmological timescale. This is where PBHs offer an elegant solution.

The Problem of Early SMBH Growth

Imagine trying to grow a giant oak tree in just a few weeks. That’s essentially the challenge that early SMBHs present for conventional formation scenarios. The Eddington limit, which dictates the maximum rate at which a black hole can accrete matter, poses a significant hurdle. Even if the first stars formed very early and were very massive (Population III stars), their remnants would typically be around tens to a few hundred solar masses. Growing these to a billion solar masses requires sustained accretion at or above the Eddington limit for hundreds of millions of years, which is difficult to achieve in the early universe’s conditions.

PBH Seeds and Accelerated Growth

If PBHs with masses of, say, $10^2$ to $10^5$ solar masses formed directly in the early universe, they could act as the “seeds” for these early SMBHs. These “intermediate-mass” PBHs would have already existed at very early times, long before the first stars formed. This effectively gives them a significant head start in the growth process.

- Earlier Formation: Unlike stellar seeds which depend on star formation, PBH seeds are formed directly from cosmic density fluctuations. They would be present much earlier than the first stars, allowing more time for accretion.

- Larger Initial Mass: Even if the initial PBH is only a few hundred solar masses, it is already a much larger seed than typical stellar remnants, reducing the amount of subsequent growth required.

- Halo Dynamics: These PBH seeds could naturally find themselves at the centers of dark matter halos, where matter densities are higher, facilitating accretion. The presence of a massive black hole could also influence gas dynamics in the halo, potentially funneling more material towards the center.

While not completely free of challenges, the PBH seeding model provides a compelling alternative to stellar seed models and is actively being investigated through simulations and observational searches. Discovering a relic PBH in the center of an early galaxy would provide strong evidence for this hypothesis.

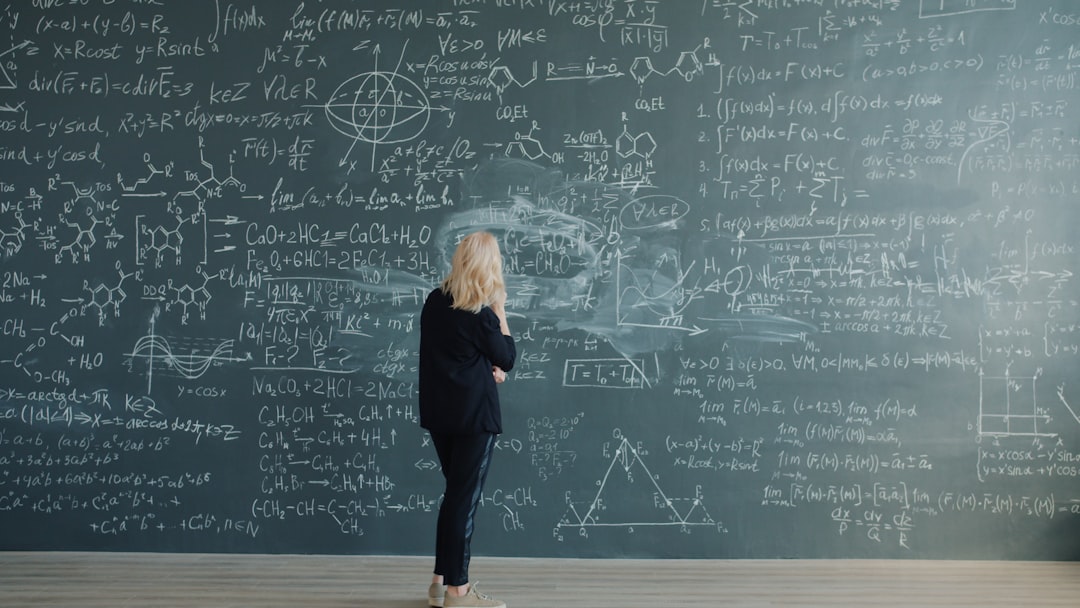

Multimessenger Observational Probes

The quest for primordial black holes is a multifaceted endeavor, spanning across the electromagnetic spectrum and beyond. Researchers employ a diverse arsenal of techniques, each sensitive to different PBH mass ranges and their unique astrophysical signatures. This multimessenger approach is crucial, as no single probe can cover the vast parameter space of possible PBH masses and abundances.

Gravitational Waves

The era of gravitational wave astronomy, inaugurated by LIGO, offers a new and exciting avenue for detecting PBHs.

- Binary Mergers: If PBHs exist in isolation or as a significant component of dark matter, they could form binary systems that eventually merge, emitting gravitational waves detectable by ground-based (LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA) and future space-based (LISA) interferometers. The masses of the black holes detected by LIGO, especially those in the “mass gap” (roughly 50-150 solar masses, a region where stellar black holes are not expected to form easily) or very light black hole mergers, could be indicative of a primordial origin. The observation of neutron star-black hole mergers is also highly informative regarding the mass distribution of compact objects.

- Stochastic Background: A population of merging PBHs throughout cosmic history would produce a continuous, albeit faint, gravitational wave background, analogous to a cosmic hum. Detecting such a background would provide strong evidence for PBHs, and its characteristics could reveal details about their mass distribution and abundance. Pulsar Timing Arrays (PTAs) are particularly suited to detect very low-frequency gravitational waves from supermassive black hole binaries, and could also be sensitive to a stochastic background from more massive PBH mergers.

Electromagnetic Radiation

While PBHs themselves are “dark,” their interactions with ordinary matter or their evaporation can produce observable electromagnetic signals.

- Accretion Signatures: PBHs accreting gas in the early universe or in present-day galaxies could produce X-ray or radio emission. Their emission properties might differ from those of stellar or supermassive black holes, potentially allowing for differentiation.

- Gamma-Ray Background: As mentioned earlier, evaporating PBHs would emit gamma rays. The non-detection of an anomalous gamma-ray background places stringent limits on the abundance of light PBHs.

- Microlensing Beyond MACHO/EROS: While existing microlensing surveys have constrained PBHs in certain mass ranges, future surveys with wider fields of view and longer observational baselines (e.g., from Rubin Observatory) could probe new mass windows and potentially detect rare microlensing events from asteroid-mass PBHs.

Other Probes

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Distortions: The presence of PBHs could influence the acoustic oscillations in the early universe, leaving subtle imprints on the cosmic microwave background. These could manifest as distortions in the CMB’s temperature and polarization anisotropies, or modifications to its spectral features.

- Neutrino Emission: Very light PBHs that evaporate entirely would also produce neutrinos in their final stages. Detectors like IceCube could potentially place limits on such events.

- Dynamical Effects on Stellar Streams and Dwarf Galaxies: A significant population of PBHs could dynamically heat up dark matter halos, disrupt stellar streams, or affect the internal velocity dispersion of dwarf galaxies in ways that differ from standard cold dark matter scenarios.

The synergistic combination of these varied observational techniques is allowing scientists to systematically explore the PBH parameter space, peeling back the layers of cosmic mystery.

Recent studies have reignited interest in primordial black holes and their potential role in the early universe, suggesting they could be a significant component of dark matter. Researchers have been exploring how these black holes might have formed shortly after the Big Bang and their implications for cosmic evolution. For a deeper dive into this fascinating topic, you can read more in this insightful article on mycosmicventures.com, which discusses the latest theories and discoveries surrounding primordial black holes.

The Broader Implications of PBHs

| Metric | Value / Range | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Range | 10^15 g to 10^5 solar masses | Estimated mass range of primordial black holes formed in the early universe |

| Formation Epoch | 10^-43 to 10^-23 seconds after Big Bang | Time period during which primordial black holes could have formed due to density fluctuations |

| Density Fluctuation Threshold | δ > 0.3 to 0.7 | Overdensity threshold in the early universe required for collapse into a primordial black hole |

| Evaporation Time | Varies from current age of universe | Time for primordial black holes to evaporate via Hawking radiation depending on mass |

| Current Abundance Limit | Less than 10% of dark matter | Constraints from observations on the fraction of dark matter that can be primordial black holes |

| Typical Radius | 10^-13 cm to kilometers | Schwarzschild radius corresponding to the mass range of primordial black holes |

| Spin Parameter | 0 to 1 (dimensionless) | Expected spin range of primordial black holes depending on formation conditions |

The existence and properties of primordial black holes extend far beyond their potential role as dark matter or SMBH seeds. They touch upon fundamental questions in cosmology, particle physics, and general relativity, acting as a powerful conceptual tool for exploring the very early universe.

Probing Beyond the Standard Model of Particle Physics

The conditions under which PBHs would form often require specific features in the early universe that might involve physics beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. For example:

- Phase Transitions: PBH formation could be enhanced during cosmological phase transitions (e.g., the electroweak phase transition or the QCD phase transition), which are periods of dramatic changes in the fundamental forces and particle content of the universe. Studying PBHs could thus provide insights into the nature and dynamics of these transitions.

- Modified Gravity: Some theories of modified gravity predict different gravitational dynamics in the early universe, which could enhance or suppress PBH formation. The non-detection or detection of PBHs could therefore constrain alternative gravity theories.

- Exotic Matter Forms: The presence of exotic forms of matter or new fields in the early universe could also influence the formation of PBH. For instance, scalar fields beyond the Higgs boson could play a role in creating the necessary overdensities.

In essence, PBHs serve as “dirty thermometers” or “cosmic pressure gauges” for the very early universe, sensitive to physical processes that are otherwise inaccessible.

Bridging Microphysics and Macrophysics

PBHs represent a fascinating intersection where the largest structures in the universe (black holes) find their origin in the smallest scales (quantum fluctuations). This bridge between microphysics and macrophysics is a fundamental aspect of theoretical cosmology. Understanding their formation mechanisms often requires a synthesis of quantum field theory in curved spacetime and general relativity.

Implications for the Anthropic Principle and Fine-Tuning

The conditions for PBH formation are sensitive to the primordial power spectrum, which itself is determined by inflationary physics. If we were to find that PBHs constitute a specific fraction of dark matter, it might impose constraints on the parameters of inflation, potentially shedding light on questions of cosmic fine-tuning and the anthropic principle. For instance, if the universe were slightly different, would PBHs form in dramatically different abundances, potentially altering the conditions for galaxy and star formation, and ultimately, life itself?

The journey to understand primordial black holes is far from over. It is a scientific expedition into the cosmic dawn, driven by theoretical predictions, ingenious observational campaigns, and the enduring human curiosity to unravel the universe’s deepest secrets. Each new constraint, each potential detection, brings us closer to painting a more complete picture of our cosmic origins and the enigmatic objects that might silently populate its vast expanse.

▶️ WARNING: The Universe Just Hit Its Limit

FAQs

What are primordial black holes?

Primordial black holes are hypothetical black holes that are believed to have formed in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang, due to high-density fluctuations in the primordial matter.

How do primordial black holes differ from black holes formed by collapsing stars?

Unlike black holes formed from the gravitational collapse of massive stars, primordial black holes could have formed directly from density variations in the early universe, potentially having a wide range of masses, including very small ones.

Why are primordial black holes important in cosmology?

Primordial black holes are important because they could provide insights into the conditions of the early universe, contribute to dark matter, and influence the formation of large-scale cosmic structures.

What evidence supports the existence of primordial black holes?

Currently, there is no direct evidence for primordial black holes, but researchers look for indirect signs such as gravitational lensing effects, gravitational waves from black hole mergers, and their potential impact on cosmic microwave background radiation.

Can primordial black holes explain dark matter?

Some theories propose that primordial black holes could make up a portion or all of dark matter, but this remains speculative and is an active area of research with ongoing observational efforts to confirm or rule out this possibility.